What Connects the Gulch and the Atlanta BeltLine? A Technocratic Financial Tool Known as Tax Increment Financing.

On a rainy evening in September of last year, hundreds of Atlantans flooded City Hall for a public process of “community engagement” around the Gulch redevelopment plan. The room was quickly filled to capacity, and many latecomers were barred from entering the small space by members of the Atlanta Police Department, stationed by the doors. What ensued was less a conversation or opportunity for community engagement than a tightly-controlled presentation by the Mayor and the Los Angeles-based developer CIM Group, the designated private “partner” for the plan. The presenters touted the plan as a “once in a generation” opportunity, and painted CIM as a benevolent benefactor, gracious enough to undertake reviving the “hole in the heart of the city.” Despite the City’s motley tactics to control the messaging — including “participation guidelines” encouraging the audience “to be objective and refrain from side conversations,” a large police presence, and limited seating — the outrage in the room was impossible to contain as protestors and long-time community activists spoke out against the plan.

Redlight the Gulch Cost Vs. Benefit Analysis

But what exactly is “the Gulch” anyway? Currently, the Gulch is the name for a 27-acre section of downtown Atlanta largely made up of parking lots and old rail lines, used by some of Atlanta’s homeless population as a sleeping space. CIM envisions redeveloping it into a “mini-city.” In CIM’s plans, the development would consist of nine million square feet of office space, 1,000 residences, 1,500 hotel rooms, and one million square feet of retail space. The total cost comes to about $5 billion, with around $2.5 billion, or half, coming from property and sales taxes over the next 30 years. The City claims the plan holds unmatched promise for Atlanta residents in the form of jobs, affordable housing, and an economic development fund, among other things, all of which have been touted through an astroturfing “Greenlight the Gulch” campaign, including robocalls, direct mailers, endorsement on the City’s official website, and a Facebook page.

Opponents of the deal, namely the Redlight the Gulch Coalition, however, point out that when you look beyond the City’s hyping of the public benefit dollars, one can see that public cost grossly overwhelms any benefit. With what the Coalition claims will be $2.5 billion in investment costs coming from public tax money and only $45 million returned in public benefit, the cost is 55 times the reward. Furthermore, the Gulch redevelopment plan entails the complete privatization of the 27-acre tract, including the roads and sidewalks, right in the middle of Atlanta’s downtown. No part of the development would be publicly owned. On November 6, 2018, the plan passed City Council, but at the time of writing, the Redlight the Gulch Coalition is appealing the bond validation process to the Georgia Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, expanding out from the Gulch in every direction, another of the City’s major public-private redevelopment projects is in motion. This one is the much more familiar and renowned Atlanta BeltLine. Unlike the Gulch, the BeltLine is not in any way hypothetical. Its development has been well underway for over twelve years. Upon first glance, the BeltLine may seem like a project of a fundamentally different variety than the Gulch. For one, the BeltLine is seen in a more positive light by many Atlanta residents, with seemingly clear public benefit in the form of increased pedestrian access to green space and the city. But it invokes similar feelings of outrage and fear for many of Atlanta’s older residents and younger activists familiar with Atlanta’s development trends, recently demonstrated not only in the Gulch, but also the City’s critical support of the Mercedes Benz Stadium in 2013 and its handing over of Turner Field to Georgia State University without a binding Community Benefits Agreement in 2017. Since breaking ground in Old Fourth Ward in 2008, the BeltLine has directly caused skyrocketing rents and property taxes. To make matters worse, the BeltLine never worked to ensure protections for lower income residents to stay in place, despite the anticipated flood of private investment and rising land values.

Tying together these two massive redevelopment efforts – the Gulch and the BeltLine – and their lack of prioritizing real public benefit for Atlanta residents, is a funding mechanism called a Tax Allocation District (TAD), also known as Tax Increment Financing (TIF). Today, TIF is a go-to tool used by municipalities across the country to leverage private sector investment for the “revitalization” of designated sections of cities.

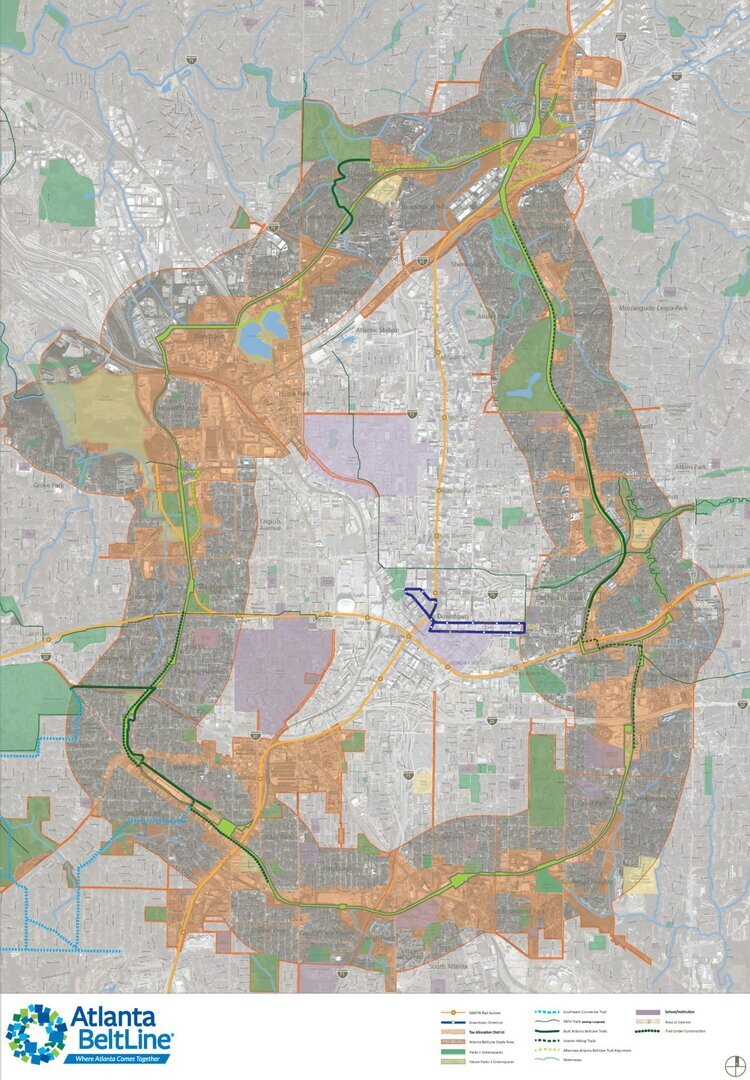

BeltLine TAD Map - beltline.org/doc_type_cat/tad/

TIF works like this: a municipality designates a special taxing jurisdiction around an area targeted for redevelopment. It then freezes taxes at their current levels, and reserves future tax increases – expected from rising property values (and sometimes increased sales tax) as a result of the redevelopment – for redevelopment costs. The municipality then sells bonds on the global bond market, secured by the dedicated stream of tax revenue. The borrowed bond money is used by the local state to re-valorize the area and make it more attractive to private investment – upgrading infrastructure, demolishing degraded buildings, starting new construction, and so on. New infrastructure induces developers to move in with promises of profitability in future rent yields and property sales. The whole TIF process rests on the assumption that public investment and commercial development will increase land values and retail, and thus revenue for local governments through property and sales taxes.

In the case of the BeltLine, bonds are used to pay for the acquisition of private property and infrastructure costs for the construction of the BeltLine itself, as well as priming surrounding areas for private construction. For the Gulch, bonds would be used to pay for infrastructure improvements and be paid for both by CIM and the City. In addition to funding from the Westside TAD, the majority of the Gulch’s funding would be from an Enterprise Zone. This is a similar financial tool to TIF, but one which secures bonds based on projected increases in sales taxes (instead of primarily property taxes) and which required approval from the State of Georgia for a sales tax exemption.

The fact that financial tools like these even exist remains unknown to many of Atlanta’s residents whose taxes fund them. They are therefore not recognized for the profound, material consequences they hold for Atlanta residents struggling with increasing rent burdens and lack of access to transportation, healthy food, and well-funded schools. It is these financial tools, in particular, their situation within a historical trajectory of state-driven reliance on financing through debt, and their implications for gentrification and displacement that this piece considers.

The Growth of Racialized Municipal Bond Markets

To understand the proliferation of TIF and its negative impact on historically disinvested areas, it’s important to look first to the history of racialized urban disinvestment that marginalized inner-city neighborhoods, and then the turn by cities towards dependency on the municipal bond market to fund urban development, infrastructural upgrades, and other basic government functions. In the middle of the 20th Century, US cities relied heavily on federal funding for urban renewal. Beginning with the Housing Act of 1949 and the amended Housing Act of 1954, municipalities were enabled to purchase large swaths of inner-city property and give enormous subsidies to private actors to incentivize redevelopment. Black neighborhoods across the country were razed for highways, commercial projects, and public housing projects in the name of slum clearance and removing urban “blight” — all funded by the federal government. In Atlanta, the population decreased by 60,000 in the 1960s as the City razed Black neighborhoods for highway construction. Nationally, between 1949 and 1965, urban renewal displacedone million people. Through the 1970s, massive amounts of federal dollars continued to be funneled into cities, used to demolish Black communities and permanently transform urban environments.

The violent roll-out of urban renewal occurred against the backdrop of decades of discriminatory mortgage lending backed by the federal government that enabled broad-based wealth accumulation for whites. With the establishment of the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933 and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) in 1934, the federal government insured private mortgages on a mass scale, making homeownership available to whites by lowering interest rates and down payments. Using the justification that there would be a higher risk of loan defaults, insurers denied these same mortgages in Black neighborhoods.

Gentrification Timeline - urbandisplacement.org/gentrification-explained

HOLC systematized this denial through the creation of maps codified primarily based on race. Black neighborhoods were coded red and denied mortgages. Furthermore, the use of restrictive covenants on properties receiving FHA-backed loans banned the sale of properties to non-whites, ensuring long-term segregation. So while federal government subsidies facilitated white wealth accumulation through mortgages, critical infrastructure required for suburbanization, and a broad shift in investment towards white areas, they simultaneously stripped Black communities of wealth. This was done first through the denial of mortgage lending and disinvestment, and then through Urban Renewal’s demolition of Black neighborhoods. The flight of whites and capital to the suburbs drastically reduced cities’ tax bases and thus locally-sourced funding for social programs and development.

Following the 1970s and Urban Renewal, cities saw massive cuts in federal funding. This was part of a major structural shift in the global economy from one based on commodity production backed by large-scale government funding of infrastructure, to one based on the appropriation of already-existing value through the privatization of public resources and the extraction of revenue through creditor-debtor relationships. The latter economic regime, commonly referred to as neoliberalism, is considered by geographer David Harvey to be a class project carried out globally beginning in the 1970s by capitalist elites to degrade labor power and the welfare state and shift wealth ever upwards through an increasing capture of previously public resources.

Financialization, or the use of financial debt instruments to accumulate capital, has been one central tool of neoliberalism. Geographer Sage Ponder describes financialization as a racialized process because it extracts value by charging impoverished people and historically disinvested and marginalized areas higher interests as a way to protect investors from these “risky” borrowers. We can see here how the label of “risk” is carried through time, first used to exclude racialized populations from legitimate credit building opportunities, then to include the same populations in predatory lending schemes. The most well-known example of financialization is the subprime mortgage lending that caused the 2008 financial crisis, but similar economic processes occur at the level of city management.

For cities, the neoliberal economic turn saw huge cuts in federal funding. Needing new sources of income, cities were forced into inter-municipal competition for the attention of private investment and the bond market, turning to “entrepreneurial” economic development strategies. On average, in 1978, 15% of city revenues come from the federal government (more than 25% for some major cities), but by 1998 less than 3% were derived from federal sources. Sage Ponder’s research shows a direct correlation between federal funding cuts and an increase in municipal debt. In the 30 years following 1981, the size of the municipal bond market increased by about $110 billion each year as cities began to buy increasing levels of debt to provide basic services like water and sewage infrastructure without any existing funds. The repayment mechanism for many bond-funded infrastructure projects relied on user fees, with disastrous consequences for some cities like Detroit, where tens of thousands of people had their water cut off when their bills became too expensive.

The reliance on bond financing has been particularly harmful to majority-Black cities. Ponder shows that the cities receiving the highest interest rates on their loans are also the cities with majority-Black populations. This trend became measurable at the turn of the century following the passing of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Modernization Act of 1999 and Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000. These acts deregulated finance and allowed commercial banks to become lenders in the market for revenue bonds (bonds backed by a specified revenue stream generated from a development project - such as the BeltLine and the Gulch).

It is in this debt-reliant setup that wealth extracted through public taxation and increased user fees is shifted from the hands of the most marginalized populations in the country into the hands of the wealthiest 0.5%, thus reconstituting racial hierarchy and marginalization. Ponder explains that we can understand financialization within the broader framework of racial capitalism: “the process by which economic value is derived (whether in the form of profit or savings) from devaluing the spaces, places, and labor of racialized groups of people.” Other examples of racial capitalism include South African apartheid, chattel slavery in the US, and imperialism.

Technocratic, Market-Based Solutions Will Not Solve Atlanta’s Housing Crisis.

By the 1990s, TIF had become the most widely used financial tool for securitizing bonds. While it is beyond the scope of this piece to speak directly to the interest rates of the loans taken out to fund the BeltLine and proposed Gulch bonds, the above discussion situates these projects within the broader context of how and why revenue bonds have proliferated since the 1980s and how this process strengthens institutionalized racial hierarchies. The City of Atlanta currently has six TADs and says that they are the City’s most valuable economic development tool, making development possible in “blighted” areas, and all the better, at “zero cost” to the City. This strong sell is false on several accounts and conceals the harm mega development projects like the Gulch and the BeltLine bring to Atlanta residents — especially low-income residents and communities of color — by accelerating gentrification and displacement.

For one, the public benefit that TIF is supposed to bring about is typically loosely defined and more often than not primarily focuses on economic growth, without any means to keep track of whom that growth benefits. Similar to urban renewal, a city must first prove an area is “blighted” before it can legislate the use of TIF and justify funneling public dollars into largely private development projects (in the case of the Gulch, the entire development will be privately owned). However, in comparison with urban renewal, there is actually less accountability in TIF. Whereas urban renewal public financing came with a certain level of accountability to address issues of social necessity such as public housing, neoliberal private development sees increased land values and commercial activity as an inherent social good that will “trickle down” to benefit everyone else, sufficient in and of itself.

As demonstrated plainly by the example of the BeltLine, TIF projects, in reality, result in the privatization of urban land, increased land values, and the consequent displacement of residents. Following the initial bond-backed investment from the City to build the path and prime the land for development, a flood of capital from private investors poured in, speculating on increased land values and looking to the prospect of high rent yields and land sales. From 2011 to 2015, neighborhoods along the BeltLine such as Adair Park, Pittsburgh, Mechanicsville, and Westview saw median sale prices jump 68 percent.

The increased desirability and demand of the area, coupled with increasing property taxes for landlords, resulted in drastically increased rents and subsequent displacement of lower-income renters. Simultaneously, low-income homeowners’ property taxes increased, often until they could no longer afford them, at which point they had, in effect, paid for their own displacement. Worse still, as one might imagine, this kind of development does not result in the arrival of greatly needed amenities for long-term residents. Instead, it results in endless upscale bars, coffee shops, and luxury apartments that cater to and profit off newcomers’ higher incomes. Many of these newcomers are able to afford what long-term residents cannot because of the decades of federally-sponsored discrimination of Black communities, investment in white wealth accumulation, and racialized financial predation, all resulting in deep racialized wealth disparities.

Furthermore, TIF is not typically implemented in cities’ most severely disinvested areas, but rather in areas already beginning to undergo gentrification. This pattern exists because severely disinvested, “long-turnover” areas do not promise the same quick return on investment. In this way, TIF continues patterns of geographically uneven flows of capital and racialized wealth disparities, while serving to legislate tax havens for huge corporate investors whose profits would otherwise be taxed for public amenities like schools and transit.

South Atlanta Annual Income - housingjusticeleague.org/b4all-report

Another Market-Based Development Tool: Inclusionary Zoning

Like TIF, Inclusionary Zoning (IZ) avoids substantively addressing issues in severely disinvested areas, and similarly uses public policy to leverage private investment coming into gentrifying areas, all the while claiming it is for “public good.” Atlanta’s first IZ ordinance went into effect for the BeltLine Overlay District in January 2018. The ordinance mandates that developers set aside 10% of their units at or below 60% of the Area Median Income or 15% of their units at or below 80% of the Area Median Income. Developers also have the option of paying an “in-lieu” fee and opting out altogether. The City justifies the mandate by arguing that public investment in the BeltLine is beneficial to private developers who should, therefore, provide “benefit” back to the community.

A big problem here is that this does not produce housing at quantities or levels of affordability even close to what is urgently needed. This is because Atlanta’s Area Median Income (AMI), a federal standard that assesses the middle point of all the incomes in an area, is based on the entire metropolitan Atlanta area. This standard encompasses a vast disparity in incomes, with South and West side neighborhoods making drastically less than Northside neighborhoods. In much of the area where the BeltLine is headed, notably subareas 10, 1, and 2, annual incomes hover just above $20,000, but IZ “affordable” housing based on AMI is only affordable to people making around $30,000 or $40,000 annually (and that’s only 10-15% of the units, the rest priced at the totally unreachable “market rate”). The vast majority of new housing is clearly not being built for current residents of these areas.

BeltLine Subareas beltline.org/progress/planning/master-planning/

The deeper issue with IZ it that it’s usually triggered by an increase in development activity or an “upzoning” (changes in zoning codes that allow for larger buildings with more rent-producing units) which suggests the loss of far more affordable housing than an IZ ordinance mandates be created. Like TIF, IZ shows how social outcomes have become something assumed to derive from the market instead of its regulation or wealth redistribution.

In Conclusion

Since the 1970s, cities have become reliant on selling bonds as a way to fulfill basic government functions and carry out development projects. This reliance puts them in a dependent relationship with a global finance industry that seeks to profit off of racialized urban geographies by extracting greater revenue from “risky,” marginalized areas, thus reconstituting racial hierarchies. Investors enter these debt relationships with the goal of profitability, seeking to evade accountability. Though in theory bond-funded projects are undertaken in the interest of existing city residents, in many cases the burden of debt repayment is placed on these very residents in the form of taxes and user fees, threatening their housing and financial security.

In the example of TIF, a widespread tool for carrying out bond-financed redevelopment, bonds are securitized with the promise of increasing land values and subsequently increasing tax revenue collected from residents. TIF is a go-to development tool in Atlanta and its effects can be seen clearly in the case of the BeltLine as lower income residents, especially on the renter-dominated south and west sides of the city, face the present reality and foreboding prospect of skyrocketing land values with no cap whatsoever on their rents. Organizing to “redlight” the Gulch development in its tracks is critical if we are to stop rampant theft of public land and dollars and shift political priority to the actual needs of communities.

Instead of accepting politically viable, market-oriented policies that continue to displace people, we need to organize for limitations on landlord power and the decommodification of housing (getting it off the speculative market). Strong limitations on landlord power can include policies like rent control and Just Cause eviction protections which limit annual rent increases to a set percentage and give tenants the right to renew their lease year after year. Rent control “decouples” any investment to an area from rising rents so that people can remain to enjoy new amenities. This is not the same as decommodification or redistribution (there is still an unbalanced power relation where a non-property-holding tenant must pay a property-holding landlord for the right to their property). However, the greatly increased stability it offers does empower tenants to organize more effectively for a radically different setup over time.